Having rebounded from the depths of the pandemic crisis, the global economy faces a critical juncture as it battles to overcome stubborn inflation and revert to more normalized monetary conditions. The commodities complex has been thrown into flux with the war in Ukraine, imperiling regions in close proximity. The challenges are well known, even if the outcomes are uncertain. As we broaden our view to emerging economies, vulnerabilities are surfacing because of inflation and currency depreciation made worse by a strong U.S. dollar. Meanwhile, China faces a financial crisis brought on by a highly leveraged, multi-decade, real estate and infrastructure-fueled growth agenda. The potential for spillover to the broader global economy depends on the extent and breadth of the pain.

Emerging Markets Debt Crisis on the Horizon?

Emerging nations have been particularly exposed to supply shocks from the pandemic and war in Ukraine. The combination of unplanned spending to combat the disease, high commodities inflation, and food supply disruptions has led to weaker growth and elevated debt-to-GDP levels. A stronger USD (in which most commodities are traded), rising interest rates, and a repricing of risk premiums (wider credit spreads) have added fuel to the fire. In some cases, the drawing down of dollar reserves in defense of the local currency has caused liquidity strains. Sri Lanka was forced to default under a punishing debt burden, along with food and fuel shortages culminating in civil unrest. Russia, Lebanon, Suriname and Zambia have also defaulted, while others are on the brink. According to the World Bank “roughly 40 low-income economies and about a half-dozen middle-income economies are either in debt distress or at high risk of it.”1

The fundamental landscape for EM is markedly different from the early 1980s when the Mexican debt crisis dragged 27 developing countries down in a rash of widespread global defaults. Today, emerging markets are divided among the larger economies (those that have imposed inflation and fiscal discipline, embraced banking sector reforms, have mostly freely floating currencies, and whose debt is primarily denominated in their local currency) and smaller, less stable countries or “frontier markets.”

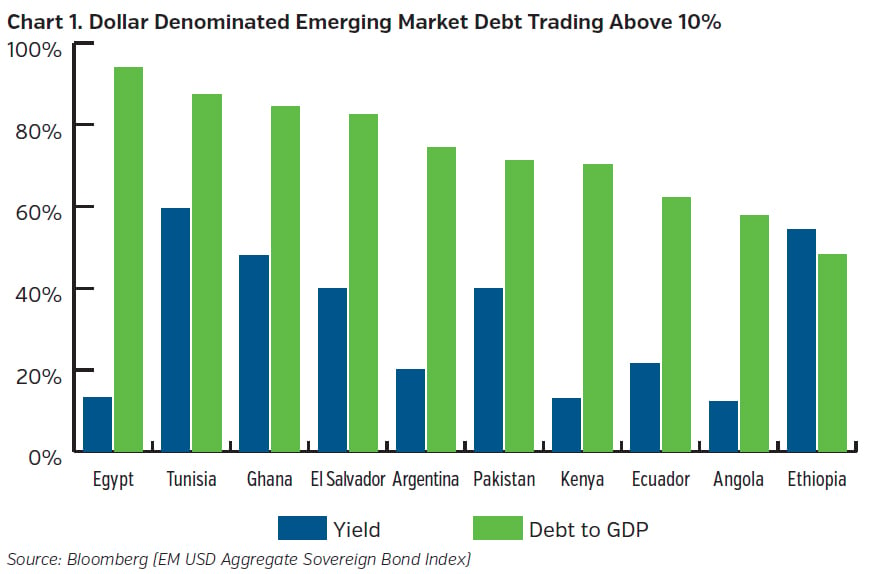

Despite the number of at-risk sovereign borrowers, the quantum of troubled foreign currency emerging market debt is unlikely to cause systemic issues of a global scale. The amount of foreign currency debt (i.e. USD, euro, yen) trading at distressed levels (yielding above 10%) stands at $237 billion, or ~17% of the $1.4 trillion in debt due to foreigners.2 Efforts by the World Bank, IMF, and other organizations to support a common restructuring framework may prove constructive compared to past debt default cycles, though the increased presence of China (known for being a less cooperative negotiating counterparty) on the global lending stage will be a new dynamic.

China Property Market: “Houses are for living in, not for Speculation”

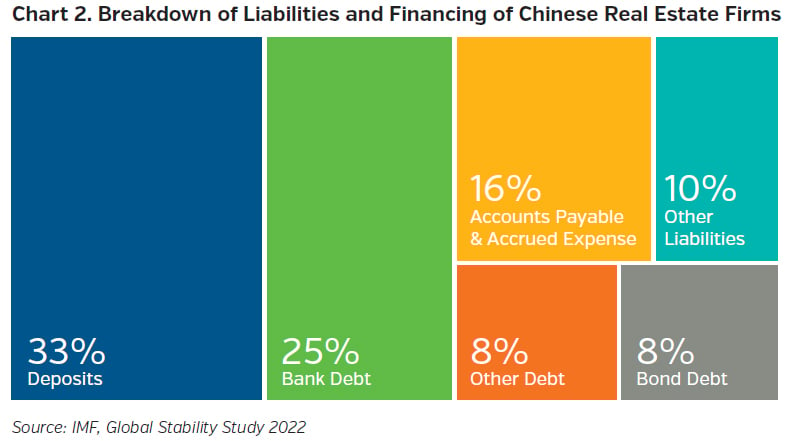

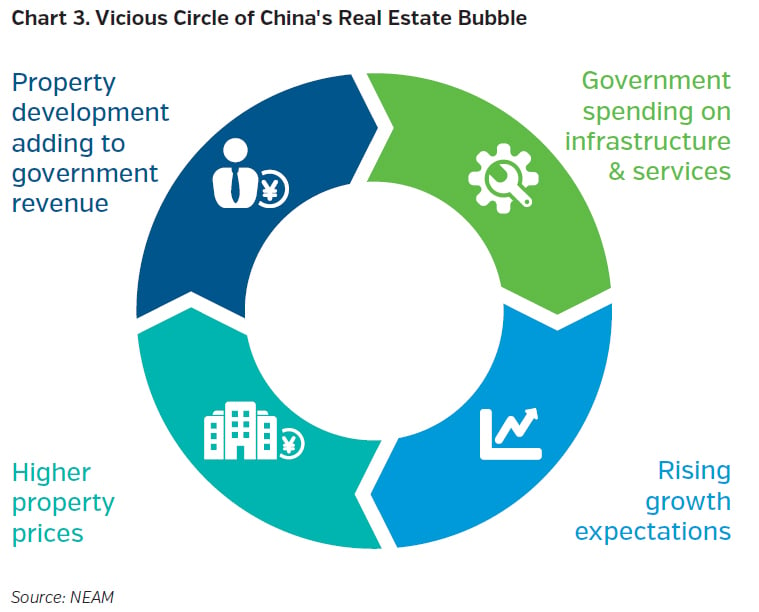

Over the past several decades, China’s supercharged growth (9% average increase in GDP from 1989 to 2021) has been fueled by a massive property boom, with housing and housing-related sectors reaching 28% of 2021 GDP. Local governments sold land to property developers, which became a key source of funding for ambitious infrastructure programs. Large scale acquisitions were financed through a combination of down payments on residences (50% of the property cost, on average), private debt (including USD denominated offshore bonds), and the debt of lightly regulated local and regional banks.

In response to increasingly speculative activity and skyrocketing prices, the Chinese government imposed new borrowing requirements (“Three Red Lines”) in 2020 that capped leverage and increased required reserves. These measures severely limited access to capital leaving property developers unable to purchase land for new projects and eventually halting construction on hundreds of thousands of units. Meanwhile, property sales have plunged by 30% in 2022 and vacancies in some urban areas have reached 20%. The situation has become quite dire amidst a loss of confidence in the sector, payment defaults by developers, sharply slowing property sales, and civil disorder as homebuyers have banded together to boycott mortgage payments for properties they do not believe will ever be completed.

The fact pattern surrounding China’s property market crisis is eerily reminiscent of the subprime mortgage crisis in the 2000s: expectations for rising prices driving real estate prices upward amidst highly leveraged risk-taking correlated across a large number and variety of entities. The key difference, however, is that banks in China are directly or indirectly state owned. This means that the property crisis is effectively contained within the country.

That is not to say that there will not be significant fallout within the People’s Republic of China involving massive consolidation among real estate firms, heavy investment losses, and a downshift in GDP growth. The government needs to re-establish stability and confidence in the housing sector, where 70% of household wealth is held (double the level of the U.S.), by ensuring the completion of unfinished homes where deposits have been made. As the government has eschewed bailouts to investors, both offshore and onshore bondholders are expected to see losses (in that order). Away from the array of lending programs and interest rate adjustment announced thus far, the problem will require a far more extensive and programmatic response to salvage the sector.

Key Takeaways

- The potential for systemic spillover from EM defaults is mitigated by the small magnitude of weak countries with foreign currency debt exposure, while China’s property crisis is contained due to state-owned backing of Chinese banking entities.

- Any transmission to financial markets will most likely take the form of increased market volatility (as in when Evergrande defaulted on debt payments) and slower global growth.

- Episodes of volatility may present an attractive entry point for U.S. fixed income investment.

- As the U.S. is a relatively closed economy (the vast majority of good and services sold is produced domestically), and driven by imports (versus exports), the flow through to U.S. GDP should be minimal.

Endnotes

1 Indermit Gill and Lee C. Buchheit, World Bank, June 27, 2022

2 “Emerging Market Bonds Face $237 Billion Cascade of Defaults": Sydney Maki, Bloomberg, July 7, 2022