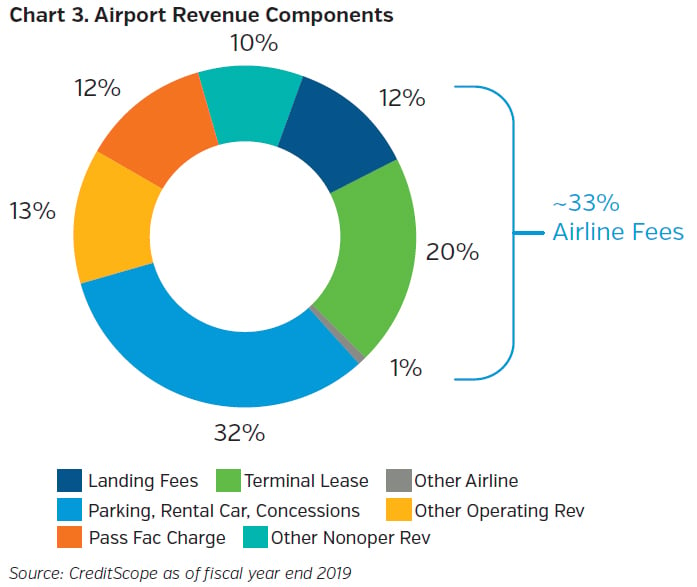

Airport bonds comprise ~4% of outstanding muni debt1 and have long been a source of incremental yield in insurance company portfolios. While economically sensitive, the sector has proven resilient through prior disruptions including 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis. Further, a rated municipal airport credit has never defaulted. The Coronavirus pandemic, however, has proven to be as great a challenge to the modern U.S. commercial aviation industry and its infrastructure as any disruption on record. By way of background, municipal airport bonds are usually secured by general operating revenues including airline fees, concessions and rents, parking fees, passenger facilities charges, etc. Airports are typically self-supporting entities that do not rely on general fund revenues of their host cities/metropolitan areas.

A Steep Descent

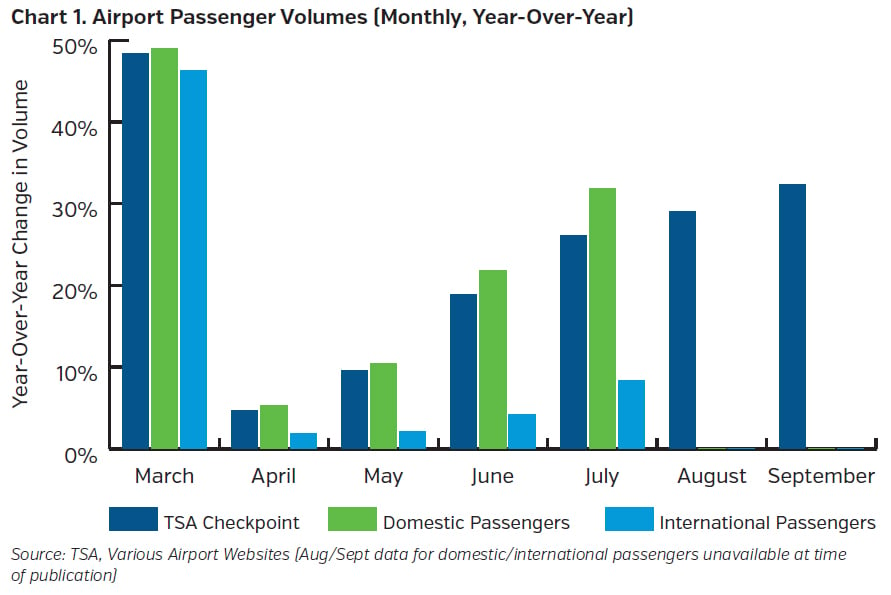

Pandemic related lockdowns, mandatory quarantines, international travel bans and a general shutdown in business travel brought air traffic to a halt in the spring of 2020. Passenger and airplane traffic both troughed in the April/May timeframe. While takeoffs and landings increased materially thru July (albeit with moderate load increases), passenger activity was more subdued. Passenger traffic changes are not related to airport size but rather the difference between the international and domestic travel cohorts. Intuitively, the broad-based international travel bans have stymied passenger recoveries while domestic travel has (slowly) begun healing. In general, airports with lower reliance on international passengers have fared better. In the aggregate, passenger volumes remain well below 2019 levels and the trend is pointing towards a multi-year recovery for the sector.

Responding to the Crisis

Ratings agencies have thus far differed in approaches to ratings migration. S&P has broadly downgraded its airport sector. Moody’s and Fitch have taken a more measured perspective, perhaps anticipating the effects of additional government stimulus.

With air and passenger traffic dropping precipitously at the advent of the pandemic, airports have pivoted towards cost containment efforts to preserve capital (refinancing debt, postponing projects, etc.). Ultimately, balance sheet liquidity and access to the capital markets will provide a salve for the extended business disruption, though financial metrics will likely take years to return to their prior strength. While airport closures are unlikely (particularly for airports in critical locations), the travel industry recovery will likely be slow and uneven. Further, the recovery is being led by domestic leisure travel while business travel recuperation will be slower, impeded by a great number of employers remaining in work-from-home mode.

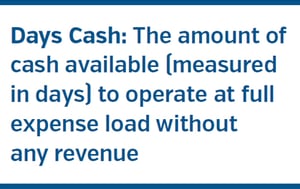

Savings For a Rainy Day

Broadly speaking, airports were in good fiscal health heading into the pandemic. Years of economic expansion created healthy balance sheets and subsequent buildups of liquidity. On average, hub-size airports had more than 450 days cash on hand (FYE-19), a measure of unrestricted liquidity that does not include Federal stimulus (CARES Act) or mandatory reserves. In other words, the average hub-sized airport could operate without reducing expenses in a zero-revenue scenario for 450 days before depleting reserves.

Airports have updated their projections since experiencing the opening salvo of the pandemic. Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport is forecast to lose $63 million (-7% margin) on an operating basis for 2020 and $34 million (-4% margin) in 2021.2 Accordingly, Miami-Dade International Airport is forecast to lose $139 million (-19% margin) in 2020 though rebounding to a positive $48 million (5% margin) for 2021.3 Importantly, these cases leave out CARES Act funding, balance sheet liquidity (above) and debt service reserves. While airports are feeling strained, balance sheet strength should provide ample cushion.

While balance sheets were in good shape, the U.S. government provided Federal support on two fronts, given the prospect of a long-term slowdown. First, $10 billion in funding (via CARES Act) was provided directly to airports based on their historical number of passengers, amount of debt, etc. Second, $32 billion was provided to passenger and cargo carriers along with certain contractors to support six months of payrolls (at 2019 levels). Importantly, airline fiscal health is intertwined with that of host airports, as airlines pay usage fees to airports (direct airline fees account for ~33% of airport operating revenues). Also, airlines can operate through bankruptcy, continuing to pay airport fees. If an airline cedes its gates (or in some manner its capacity at a specific airport), the airport authority can transfer that capacity to other airlines, correspondingly reassigning the revenue responsibility.

Access to Capital Markets

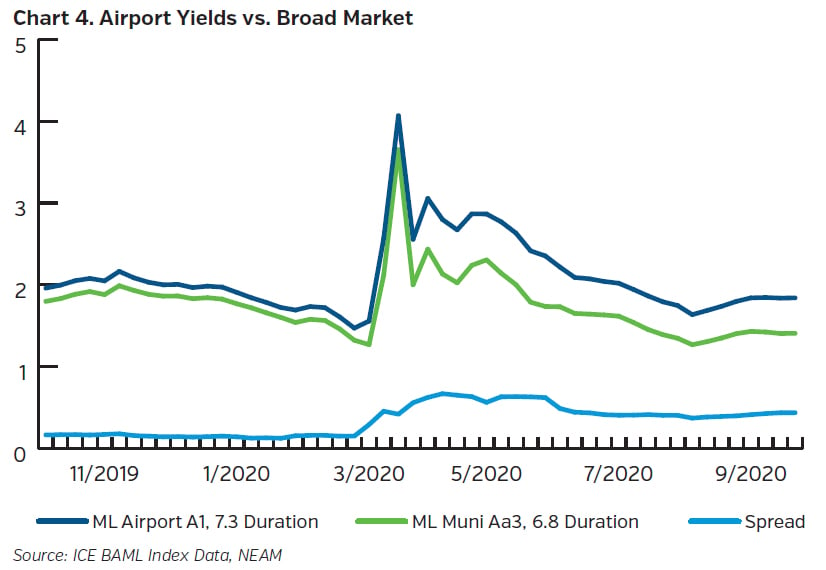

Relative to the broader municipal bond market, it is more expensive for airports to issue debt now than prior to the pandemic. While observed yields between airports and the broad market widened from 15 to 65 basis points (for tax-advantaged munis) at the height of the tumult, the differential is currently averaging 40 basis points. Though most industry experts are calling for a long, protracted airport recovery, many airports have successfully accessed the market during the pandemic, selling bonds into strong demand.

Long Runway Ahead

The path to airport credit amelioration is directly correlated with pandemic risk abatement. Broad based recovery needs domestic and international travel to revive, as well as genuine reacceptance of work-related travel and continued improvement in leisure travel. Having said this, the U.S. government may have signaled (through Federal support) airports as too important to fail. However, airports broadly came into the pandemic with strong balance sheets on the back of a multi-year economic expansion. We continue to underwrite what we believe to be leading airports which support vibrant economies, where gate demand is accordingly elevated. We are more circumspect on narrow revenue pledges, such as those secured by passenger facilities charges alone, preferring broader general revenue security. The sector should slowly repair, albeit with tepid near-term growth and weaker aggregate balance sheet metrics in the short to intermediate term.

Key Takeaways

- Airport bonds have a difficult backdrop, and as such we continue to focus our investments in airports we believe have the scale and liquidity to survive the pandemic

- Passenger traffic is suppressed, domestic travel has shown modest signs of recovery while international remains low

- Spreads are wider, though airports retain access to the capital markets

- The Federal government signaled early support for national airport infrastructure (airports and airlines)

- The sector’s recovery will likely be slow and multi-year in length

Endnotes

1 Bloomberg, ML Muni Master U0A0

2 www.dfwairport.com

3 EMMA MSRB