The Fed Then…

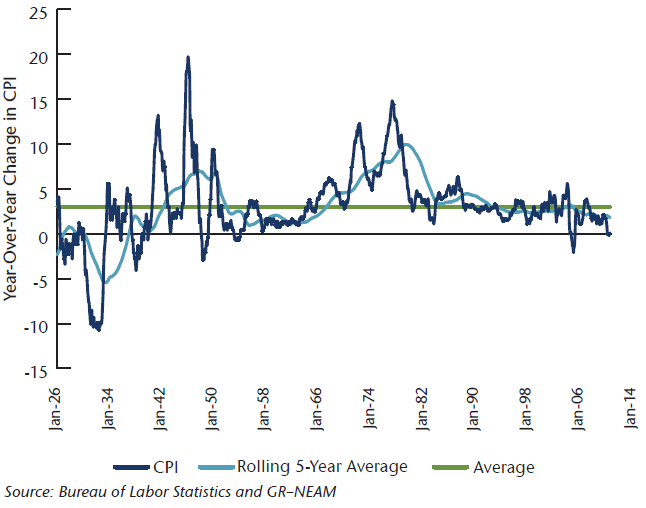

As 2015 marches on, we draw closer to the first rate hike by the U.S. Central bank in nearly a decade. This time, however, the rate hikes that will eventually occur have a decidedly different flavor than those from previous cycles. From the 1970s through the mid 2000s, the Federal Reserve was fighting a different war. As price levels moved higher during the 1970s and early 80s, the Fed’s role was largely that of inflation fighter. Even throughout the late 1980s and 90s, long after inflationary pressures had leveled off, the Fed sought to err on the side of caution in an effort to maintain price stability by staying “ahead of the curve.” It was not always successful in this regard, but one thing remained clear – the Fed was keenly aware of building price pressures. It fought many battles and ultimately won the war (see Chart 1).

Chart 1. U.S. Inflation Since 1921

The Fed Now…

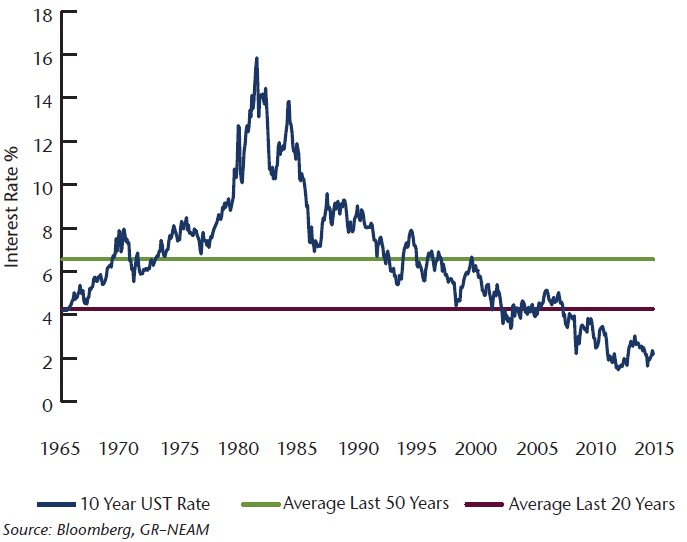

At times, battles with inflation have created significant angst and resulted in sharp and sometimes violent adjustments in the capital markets. That said, the tools available to central banks are generally quite effective in staving off inflationary pressure. After all, applying the brakes by increasing the cost of credit is indisputably effective in slowing down economic activity and keeping price levels in check. Over the last several decades, however, the cumulative effect of many factors has changed the rules of engagement and by the mid 2000s, the very nature of the game had changed. After a debt-fueled housing binge with little or no regard for mortgage underwriting standards, the global economy found itself dealing with exceptional levels of debt and aging populations, both of which conspired to make the job of spurring aggregate demand all the more difficult. Despite the massive, coordinated monetary policy response engineered by the world’s central bankers, advanced economies still find themselves with interest rates that are remarkably low relative to historical levels.

Chart 2. U.S. Treasury Yields: 1965–2015

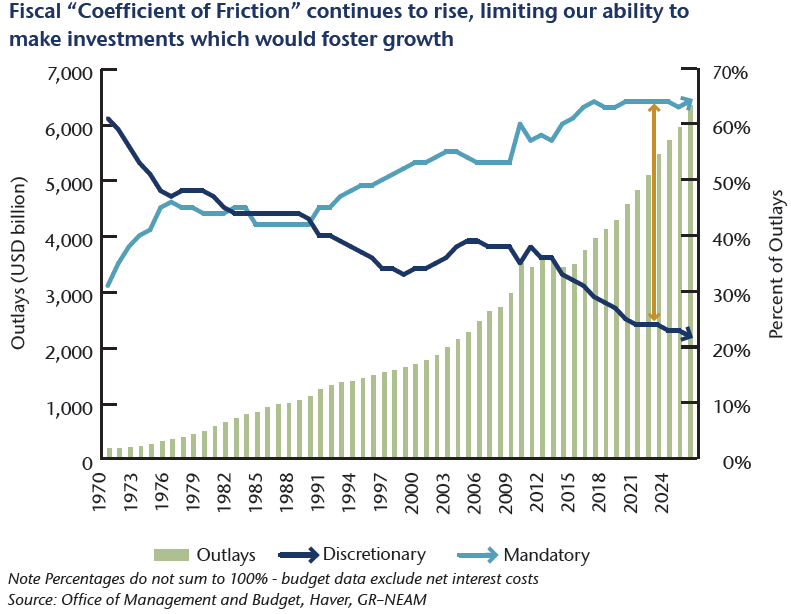

We cannot and should not discount the possibility that we are still feeling the residual effects of the cathartic 2008–2009 crisis and that eventually, global growth will gather enough momentum to shift the focus of central banks back to inflation fighting. For now, however, the battles being waged involve a fight against disinflation. As effective as monetary policy is in taming upward price pressures, its ability to prevent disinflation or outright deflation is more limited. The natural boundary of zero interest rates creates an obvious line of demarcation. As central bankers approach that line, the marginal economic benefit of further rate reductions becomes negligible. Many advanced economies now find themselves pressed up against this zero bound. While this monetary policy stance has been supportive of financial markets and has helped replenish capital lost during the financial crisis, it hasn’t spurred the strong economic resurgence many had hoped for. Additionally, we note that the fiscal flexibility of the U.S. is much more limited than it was during the Volcker Era. An aging population, the corresponding increase in social safety net costs and high debt levels have conspired to limit our growth trajectory (see Chart 3). In sum, monetary policy alone has not been enough to boost aggregate demand. With our fiscal flexibility limited and a Congress that can agree on precious little, we would suggest that this backdrop (while not necessarily permanent) isn’t likely to change in the near term.

Chart 3. U.S. Budget Expenditures

We have asserted for several quarters that the Fed would more than likely begin this process in 2H 2015. The economic data supports it and Fed guidance has pointed to this as the anticipated timing. While economic data releases will be reviewed and incorporated into the Fed’s decision, perhaps the most important factor in setting a course will be capital market stability. The pace of rate changes, when they do begin, will be very measured and judicious. While we still have a flattening bias for the yield curve over the longer term, in the near term we think the Fed will make every effort to maintain a positive slope. This is a different circumstance from previous policy cycles and wholly appropriate because, for the moment, they are fighting a different enemy.

Conclusion

Capital market volatility notwithstanding, we think one rate hike is likely in 2015 and perhaps 3 to 4 more in 2016 as the Fed attempts to normalize the front end of the yield curve. If we’re correct, the front end is vulnerable. However, if financial market volatility becomes significant enough, it may convince the Fed to wait. The markets are certainly discounting a slower Fed reaction function for this cycle and in general, we agree with this assertion. Despite the onset of “normalization,” U.S. monetary policy will remain quite accommodative in the short to medium term, providing conditions which are generally favorable (or at least benign) for risk assets.