Investors are becoming increasingly concerned about prospects for higher levels of both inflation and interest rates, resulting in the recent spate of volatility and a correction in equity prices (a 10% decline from its 52 week high). Major central banks, led by the Federal Reserve in the United States, have begun to take their collective foot off the gas with regard to the use of their balance sheets to support prices of securities in the capital markets. Investors are asking: how will the reduced buying by major central banks impact the demand for fixed income securities, interest rate levels and the shape of yield curves?

Beginnings of Quantitative Easing

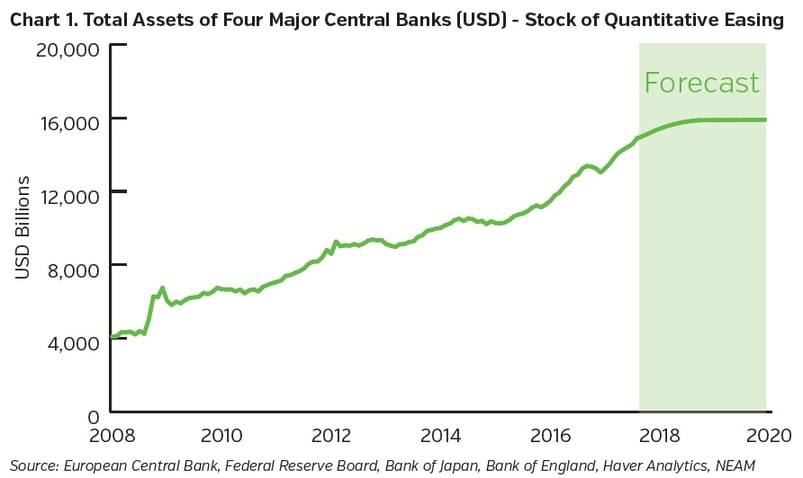

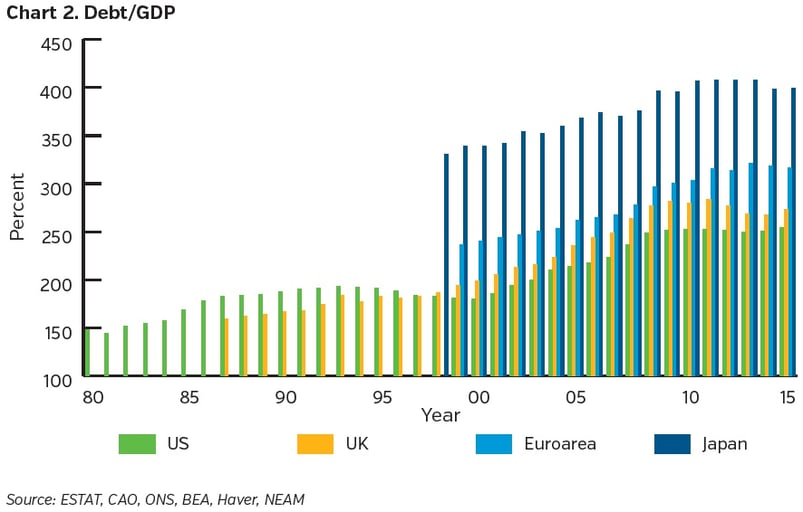

It might be helpful to start with a bit of a walk down memory lane. After the financial crisis of 2008, the four major global central banks (US, ECB, Japan, UK) engaged in significant quantitative easing (QE) by purchasing high-quality, fixed income securities on the open markets. The main goals of QE were to provide liquidity to the capital markets and maintain downward pressure on bond yields. In addition, central banks reduced their main lending rates and deposit rates. Starting in December 2008, the Federal Reserve began a series of QE programs that resulted in an increase in the Fed’s balance sheet from around $1 trillion to approximately $4.3 trillion today ($2.5 trillion in Treasuries and $1.8 trillion in MBS). In the case of the ECB, in June 2014 the bank cut its deposit rate below zero while continuing its open market purchases of securities. (Yep, institutions actually paid the bank to hold their money.) The end result of the past nine years of QE has been significant growth in central bank balance sheets and unfortunately, no progress from governments in dealing with their larger fiscal problems (Chart 1). Debt/GDP has grown to all-time highs in many developed countries and productivity has been well below long term averages (Chart 2).

Impact of Quantitative Easing

Although the last 10 years have represented the slowest recovery from an economic downturn since World War II, GDP growth has been positive and employment has rebounded both here in the United States as well as in other large developed areas such as Japan and the Eurozone. 2017 was the first year since 2010 when advanced and emerging economies accelerated in tandem. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that the world’s seven largest economies each grew more than 1.5% in 2017. That is highly uncommon. In addition, none of the major economies went in to recession in 2017 and all 45 major economies tracked by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) were growing at the same time in 2017. That is the first time this has occurred since the financial crisis. Lastly, 85% of the world’s nations increased their exports last year, the highest on record. Global growth has surely hit a sweet spot here in early 2018. Ultra low interest rates have allowed borrowers of all types to finance their rebuilding, growth and financial engineering with virtually free money.

Now what?

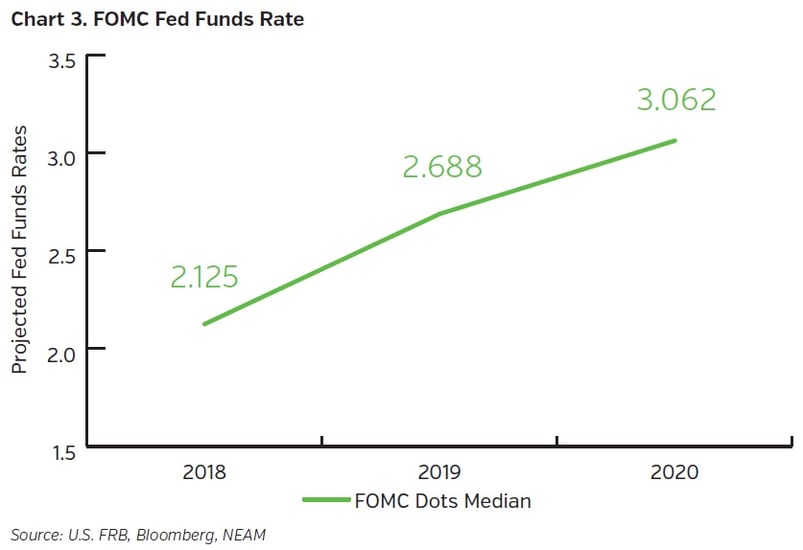

Much like we know trees do not grow to the sky, we also know all parties must come to an end. Starting in December 2015, the Fed began to slowly turn the party lights out with its first interest rate increase since the great recession. In June 2017, the Fed announced a plan to begin reducing the size of its balance sheet in a step up fashion over the next four years. The Fed has continued on this dual tightening path during 2017 and expectations are for 3 to 4 Federal Funds rate hikes this year, starting in March, and 2 rate hikes in 2019 (Chart 3).

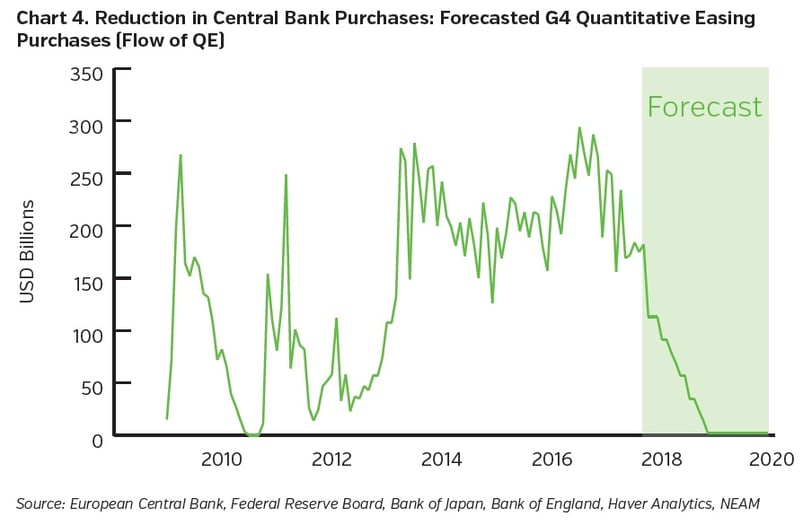

Turning our attention outside the United States, the ECB is continuing its monthly purchases of €30 billion until the end of September and then is expected to end their QE program. (Maturing securities will be reinvested so no major balance sheet reduction.) Rate hikes are expected to begin in 2019. In the UK, despite the headwinds of Brexit, the BoE raised rates in November for first time in 10 years and have signaled more to come. The Bank of Japan remains the outlier with no plans at this time to reduce the size of its balance sheet. (Actually the growth of the BoJ balance sheet in 2018 is expected to be almost entirely offset by reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet.) The cumulative impact of the end of global QE is expected to be that asset purchases by the four major central banks will shrink by more than 70% by the end of 2018 to around $50 billion/month after peaking at $182 billion/month in March 2017. The Fed balance sheet alone is expected to shrink to $2.5 trillion by 2021 (Chart 4). For the past 9 years, Central Banks have been the central support system for markets and economies. We are now in a period of transition back to letting other players – namely individuals, companies and governments–shape the path of the economy and markets.

- Of the four major central banks, only the Fed is expected to shrink its balance sheet in 2018.

- Global central banks are expected to continue to provide support for risk assets in 2018 but less than in 2017.

- Major central banks will continue to be measured with regards to raising rates.

- With “normalization” of interest rates comes normalization of market volatility which has been suppressed by QE for many years.

- Although central bank balance sheet reductions could create upwards pressure on spreads, we believe demand from other buying bases like banks and institutional investors will mitigate these spread pressures.

- US yield curve should move somewhat higher and continue to flatten from the front-end. Base case projections of 3.25 to 3.50% on UST 10-year bond for year-end 2018.

- New leadership at Federal Reserve is expected to continue to remove policy accommodation at a measured pace consistent with the Yellen era.