No Bright Lines

Since the financial crisis in 2008/2009, the lines between Central Banks and elected political officials have become increasingly blurred. The issuance of trillions of dollar, euro and yen denominated debt, much of which has been absorbed by Central Bank (CB) balance sheets, has brought the question of CB independence into bold relief. In this article, we briefly discuss the current “joined at the hip” nature of central banks, fiscal authorities and elected officials by citing a few prominent examples.

Europe: Fiscal and Monetary Convergence

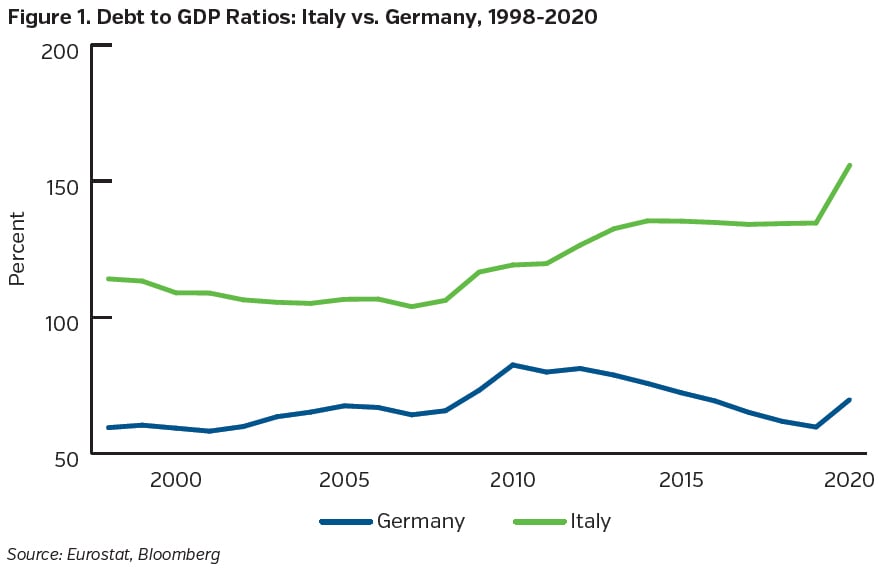

The Euro Area was designed as a monetary union but not a fiscal union. Figure 1 illustrates that countries entered the Euro Area in 1999 with vastly different levels of debt.

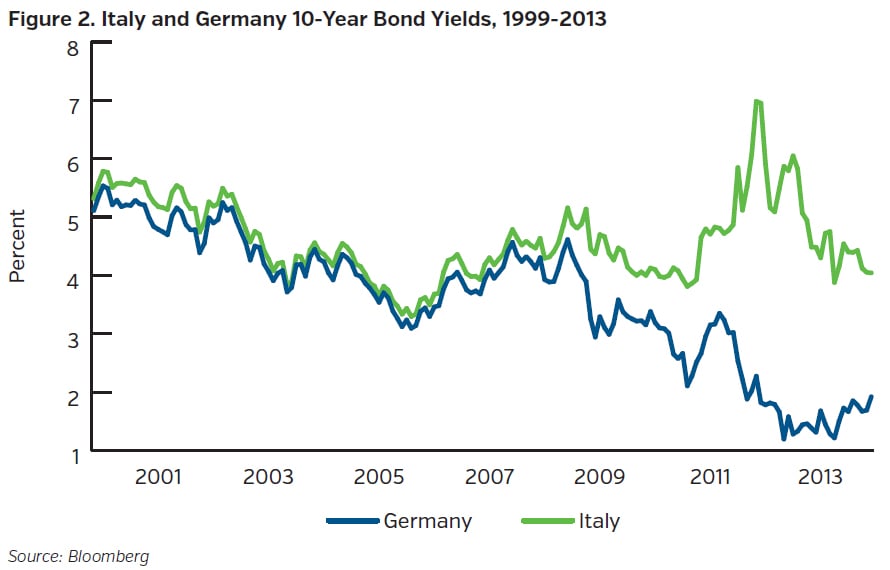

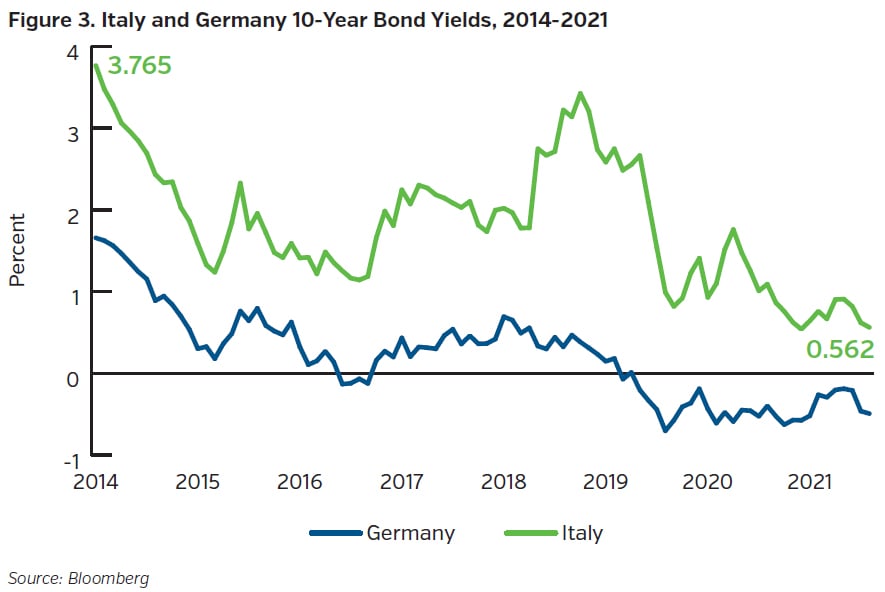

In the initial years of the Euro Area’s existence, bond investors were willing to accept narrowing yield differentials between fiscally stronger countries (e.g. Germany) and weaker ones (e.g. Italy) on the basis that currency risk had been eliminated. The global financial crisis began to change investors views of both the currency and default risk of fiscally weaker countries, as yield differentials increased dramatically. Figure 2 illustrates that by 2012, following restructuring losses inflicted on holders of Greek sovereign bonds, contagion risk had spread dramatically to Italy. In the summer of 2012 Mario Draghi, then head of the European Central Bank (ECB), made his famous “whatever it takes” speech that marked the beginning of the end of the Euro Area sovereign debt crisis. Ultimately, “what it took” was massive sovereign debt purchases by the ECB. This quantitative easing continues today in Europe and across the globe. The rest, as they say, is history (see Figure 3). As a result of the various ECB government bond buying programmes, the ECB (through national central banks) now holds close to 30% of outstanding member state public debt.

Super Mario Returns for an Encore

Mario Draghi is perhaps the most widely known leader the ECB has had since the introduction of Europe’s single currency in 1999. He became ECB President in November 2011. The global financial crisis had morphed into a Euro Area sovereign debt crisis and his task was to convince financial markets that the ECB was a credible lender of last resort to Euro Area sovereigns that were having difficulty obtaining funding from private sector investors. The support packages Draghi developed for the Euro Area sovereign bond market were eventually successful in reducing financial market stress. Monetary support from the ECB, however, was accompanied by reduced fiscal spending or “austerity” as it became known. The policy mix in the Euro Area (and elsewhere to some extent) involved exceptionally accommodative monetary policy and tighter fiscal policy in an effort to reduce sovereign debt metrics that had increased in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Draghi’s term as ECB President ended in October 2019 but he has re-emerged on the world stage recently as Prime Minister of Italy. Draghi, now working from the fiscal side of the equation, has become a staunch advocate of fiscal expansion while also keeping the monetary printing presses humming. This is in marked contrast to the fiscal cuts required of Euro Area member states when Draghi was President of the ECB. Debt ratios are apparently a quaint concern of the past.

Trump, Powell and the Return of Janet Yellen

During 2018 and into 2019, then President Donald Trump seemingly went out of his way to criticize Jay Powell, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, who he himself had appointed. Pointing to the ECB's monetary policy, Trump famously quipped that he too wanted the “gift” of negative rates that had been bestowed on other countries. After a tumultuous end to 2018, the Fed reversed course and eased policy but evidently not rapidly enough for Mr. Trump, who continued to exert enormous pressure, even if only for political purposes. The notion of politicians pressuring central bankers, particularly around elections, is not at all new but with Twitter as his megaphone, Trump certainly seemed to be wielding a cudgel in broad daylight. In the end, the pandemic rendered that wrangling moot, and the Fed embarked on a round of quantitative easing that, in retrospect, has made the original post financial crisis QE programs look like child’s play. Hence the ECB, the Fed, and other price insensitive CBs are absorbing a tremendous amount of sovereign, corporate and mortgage debt in an effort to keep the financial system awash with liquidity while at the same time (and somewhat counterintuitively), keeping interest rates low as economies recover.

No sooner did President Biden win the 2020 election than did he appoint Janet Yellen, Powell’s predecessor at the Fed, to run the U.S. Treasury Department. There you have it, poetic in its simplicity: A former Fed Chair in charge of issuing U.S. Debt and the current Fed Chair in charge of buying it, both working in concert with one another. Both of these individuals are eminently qualified. That is not the point. Rather, the point is that it is difficult to accept the assertion of an “independent” CB when a sovereign becomes so reliant on that institution to create money from thin air in order to buy debt to fund fiscal programs at sufficiently low interest rates.

Where do We Go from Here?

The longer-term issue for the Fed, ECB and other central banks is that current public debt ratios will remain sustainable as long as bond yields remain at historically low levels. How would or could central bankers react to a sustained increase in inflation above target when reducing bond purchases and/or raising rates would amplify concerns of sovereign debt sustainability? Draghi, his successor Christine Lagarde, Powell, Yellen, et al., know they have a window to take advantage of greater fiscal spending to jolt the trend growth rate higher, knowing full well that stronger growth will ultimately be needed to support any future increases in bond yields.

Key Takeaways

- Central Banks, touting their independence over the years, have seemingly become the financiers of first resort vs. last resort.

- While details are beyond the scope of this brief note, the “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT) experiment is underway. Despite being criticized as nonsense by most Central Bankers, current policy in many countries walks, talks and quacks like an MMT duck. Hence, it’s reasonable to conclude that it IS a duck.

- Rate suppression by central bankers continues to keep real rates deep in negative territory. As a result, yields globally remain illogically low and spreads exceptionally tight. While U.S. markets exhibit these characteristics as well, absolute rates/yields in the U.S. continue to attract attention because they are far higher than those available in Europe, the UK or Japan.

While this scheme may go on for a long time, it seems logical that central bankers would try to maintain as much steepness as practical in global yield curves, all else equal. Hence, we view the recent pronounced flattening with caution and, for now, have focused both U.S. and international purchase activity in the short to intermediate part of the yield curve.