Introduction

Since 2010, stability in the euro area has been tested on several occasions as many peripheral nations have undergone periods of economic and market stress. In response, European authorities have put forward proposals to make the monetary union more resilient. Completing the Banking Union, developing the European fiscal framework and providing euro area stabilisation tools to deal with large asymmetric shocks are among the topics that have been discussed. A key issue that has been repeatedly mentioned has also been the lack of a euro area-wide ”safe asset.”

A safe asset is characterised as a liquid asset that maintains value during adverse systemic crises. U.S. Treasury bonds performed this function for the U.S. economy and its banking sector during the 2008-2009 crisis, as savers in need of a vehicle to store their wealth and domestic financial institutions looking to satisfy regulations and to post collateral in financial operations were able to purchase Treasuries. In general, safe assets in the form of government bonds can retain that status as long as the government’s fiscal policy is sustainable and the central bank stands ready to play a backstop role in the sovereign debt market as a lender of last resort. In the euro area, as national crises came to the fore from 2010 onwards, it became apparent that these conditions could not be met by individual sovereigns. Deep fragmentations between the public finances of particular euro area governments and a common monetary policy across the bloc that prevented the European Central Bank (ECB) from stepping in and offering a backstop to sovereigns at crucial moments, led many investors to doubt the liquidity and solvency of the debt of many peripheral nations. This caused wide discrepancies in funding costs for sovereigns and conversely banks across euro area nations and compromised the “safe asset” status of individual nation government bonds.

How to generate a Safe Asset

While further reform of the economic and monetary union in the single currency zone is ongoing, a number of proposals have been put forward to tackle the issue of the lack of a universal safe asset. These have included debt-mutualising fully guaranteed Eurobonds, so-called Blue and Red bonds, and sovereign-backed securitised bonds. Of all the different proposed alternatives, Sovereign Bond-Backed Securities (SBBS) seemed to be the most politically palatable and a detailed paper was put forward by a task force from the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) in January 2018. Following this proposal, in May 2018 the European Commission officially declared their intent to enable the development of a market for SBBS.1

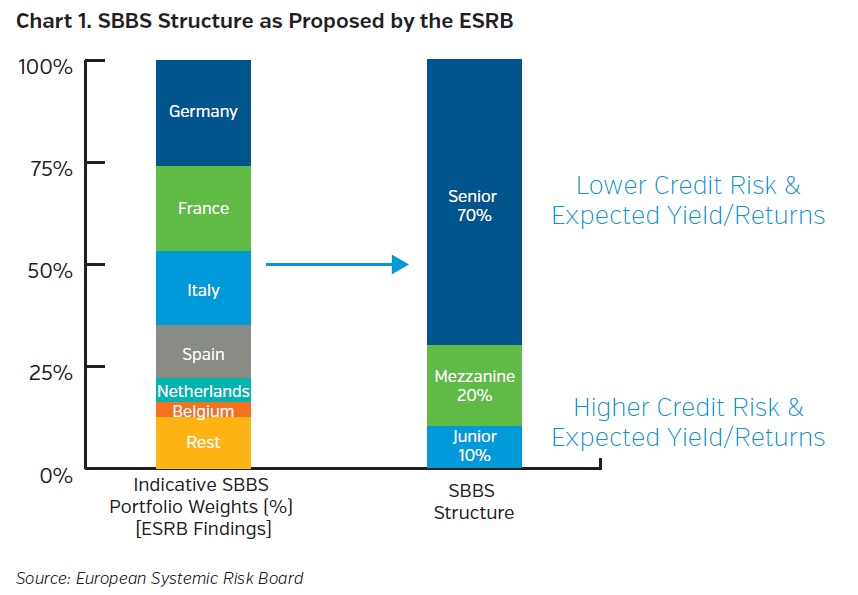

The concept outlined by the ESRB of an SBBS could be likened to a simple CDO structure of already existing euro-denominated sovereign debt issued by euro area sovereigns. The paper proposes that existing sovereign liabilities would be repackaged and then sold back into the market in three tranches of descending seniority. Currently, the task force recommends that to achieve the policy objective of creating a low-risk security, the senior layer should be 70% thick, followed by 30% of subordinated securities to be divided into a 20% thick mezzanine security and a 10% thick junior security (see Chart 1). Like other securitised instruments, holders of the most subordinate tranche would bear the first losses and the more senior tranches would be protected from losses, as predetermined by a contractually-defined cash flow waterfall.

SBBS portfolio weights would be determined by the ECB capital key which is well-defined and institutionalised as a measure of EU Member States’ economic significance. Currently, the ECB has been using the capital key to guide the percentage share of government bonds purchased under their quantitative easing programme. The paper also recommends that only bonds where the sovereign has primary market access be included. This would, therefore, exclude bonds of any country placed into a debt restructuring programme. Greece is a notable example of this after the country’s bailouts in 2010, 2012, and 2015.

As SBBS would combine elements of sovereign bonds and securitised products, SBBS would be issued by a dedicated independently established entity with no previous trading or indebtedness and would simply be a pass-through vehicle. The sole function of this entity would then be to manage the cash flows accruing to the sovereign bond positions and pass them onto SBBS investors. There could be multiple private sector arrangers, a single public sector arranger or both according to the official proposal.

Next Steps

The findings from the ESRB show that they believe a market for these new securities could be introduced gradually. While building a marketplace for securities from scratch is no easy task, the aim is that it would be initially driven by investor demand and if the securities prove popular, the market could grow. One of the key aspects outlined in the report that would need to be changed to promote new SBBS is the regulatory treatment of said securities. Prevailing regulations were not conceived with the unique properties of SBBS in mind. Despite the underlying assets being well-known to market participants as they are some of the most widely traded securities in the euro-area, SBBS would currently receive an unfavourable treatment compared with domestic sovereign bonds in terms of capital and liquidity requirements. Under both Basel III and Solvency II, sovereign bonds have a zero-risk weight and this would put SBBS at a disadvantage.

Reaction/Opposition

While trying to tackle the “safe asset” issue, the SBBS proposition has not sufficiently resolved the political issues surrounding the creation of such an asset. As there is no unified fiscal policy within the euro area, to complement the more comprehensive monetary union, many commentators have been concerned about possible debt-mutualisation or risk-sharing in the euro area. As a result, the proposal was politically unpalatable to officials from traditionally fiscally responsible nations like Germany, who are fearful that their taxpayers could end up being responsible for the debt of other nations. The primary concern from economists and officials who oppose the idea is that the creation of SBBS will engender joint liability for the securities in the future or in the event of any adverse market shock and that the securitisation of government debt creates new complexity and risk. From their standpoint, it still remains more prudent to resolve the structural fiscal problems of member countries rather than tackle the issue of the lack of a “safe asset.”

Public debt management agencies have also been slow to throw support behind the idea. Concerns have focused on the consequential impact on bonds that are not included in the packaged securities, should the newer SBBS market begin to dwarf the existing traditional markets. As the market is untested, there is the fear that “residual bonds” (i.e. bonds not included in an SBBS) could be adversely impacted and that there could be other unintended consequences that disrupt the functioning of local government debt markets if two separate markets were to develop. Rating agencies S&P,2 Fitch3 and Scope4 have all released reports outlining their concerns over the structure. In general, the idea of an SBBS provides a small credit boost to the securities but the high correlation of euro area sovereign default risk could prevent them being rated as highly as the highest rated government debt in the bloc.

- The SBBS proposal is the one most advanced by European authorities to generate a “safe asset” for the single currency bloc that would not require any guarantees or additional revenue commitments on the side of member states.

- SBBS are still just an idea. Regulatory changes to enable SBBS and consequential market demand for such securities will determine their eventual validity.

- Current Solvency II rules would hinder demand for SBBS from insurance companies.

- While there are many more steps to be taken before SBBS can become a reality, given the potential significance of such a development NEAM will continue to monitor the evolution of SBBS or SBBS-like securities and will be in contact with clients should this market develop.

Endnotes

1 “Sovereign Bond-Backed Securities (SBBS).” European Commission.

2 Frankfurt, Moritz K. “Article Outlines Approach To Assessing European ‘Safe’ Bonds (ESBies).” S&P Global Ratings: Ratings Direct. 25 April 2017.

3 Chrysoloras, Nikos, and Alexander Weber. "EU Unveils Pooled Sovereign-Debt Plan Amid German Resistance." Bloomberg. 24 May 2018.

4 “Scope: Can Sovereign Bond-Backed Securities be the Safe Asset the Euro Area Wants?” Scope Ratings. 7 June 2018.