The Legacy of Financial Engineering

The S&P 500 finished the year trading at virtually the same level where it began. This might lead one to conclude that 2015 was an uneventful year. It was just the contrary as volatility inducing events abounded. The market had to contend with Greece nearly exiting the euro, China accomplishing a shock devaluation of its currency, U.S. corporate earnings contracting, severe compression in the price of oil and other parts of the commodity complex, and the Federal Reserve raising interest rates for the first time in nearly a decade.

This backdrop encouraged indecision, and risk assets traded in a narrow band, barring the August correction when the index fell more than 10% from its May high. Investors endorsed a small subset of companies, resulting in exceptionally narrow market breadth. As a result, the mean performance for stocks within the S&P 500 index was down over 3%. Suffice it to say, returns were difficult to generate as price earnings multiple expansion, a key driver of market gains in 2014, could not overcome the earnings malaise and global cross currents, and the market treaded water.

With this retrospective in hand, we turn our attention to 2016 with some circumspection. While the future is by definition uncertain, it is undoubtedly impacted by the actions of the recent past. This holds especially true for the capital markets amidst the steady path of “financial engineering” that has taken place. Low interest rates have enabled companies to issue record levels of debt to fund mergers and acquisitions as well as shareholder friendly actions. These strategies, termed financial engineering, are non-operational in nature and typically inject liquidity. There are consequences to this liquidity: suppressed volatility, potential misallocation of capital, and overstated earnings. While there has been a measurable benefit to risk assets, imbalances have also built, and the asset productivity of corporate America has declined. In our view, capital allocation and asset productivity, as key long term determinants of equity valuations, should garner increased investor attention as central bank liquidity is drained from the U.S. market.

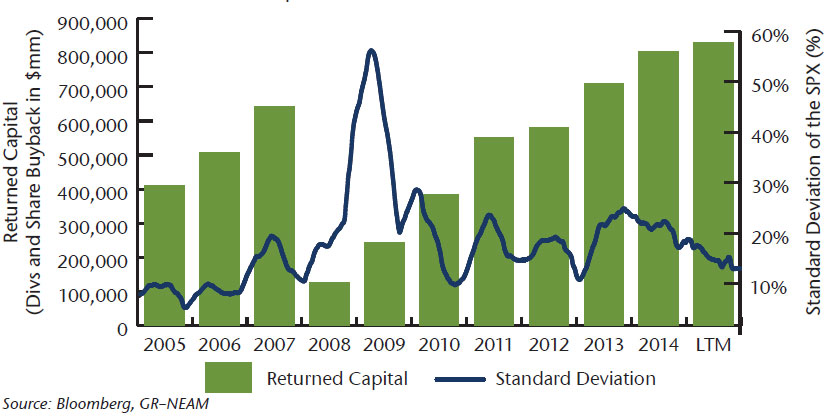

Corporate leverage exemplifies the magnitude of financial engineering that has transpired. More specifically, total debt for companies within the S&P 500 (excluding financials) has doubled versus pre-crisis levels while EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization) has risen by roughly half of this magnitude. Proceeds have been used to finance generous dividend payments, to fund share buyback programs and to pursue deals to create inorganic growth. Illustratively, global M&A for 2015 reached a record $4.7 trillion in value, according to preliminary figures by Thomson Reuters, and tallies in the U.S. are set to exceed the previous record set in 2007. Likewise, the absolute dollar level of returned capital, defined as dividends paid and net capital stock, will rise again in 2015 after having doubled over the last decade and posting noteworthy acceleration in recent years.

This velocity of returned capital has suppressed stock volatility. Volatility, as measured by the standard deviation of the market, has been falling, in part, as corporations act as price inelastic buyers of their own shares. The corporation is the incremental buyer, providing an underlying bid in the market smoothing fluctuations (Chart 1) and driving prices higher by absorbing supply. According to data compiled by Goldman Sachs, more than 80% of S&P 500 firms engage in share repurchase which is almost double the rate of firms purchasing shares roughly 20 years ago.

Chart 1. S&P 500 Returned Capital

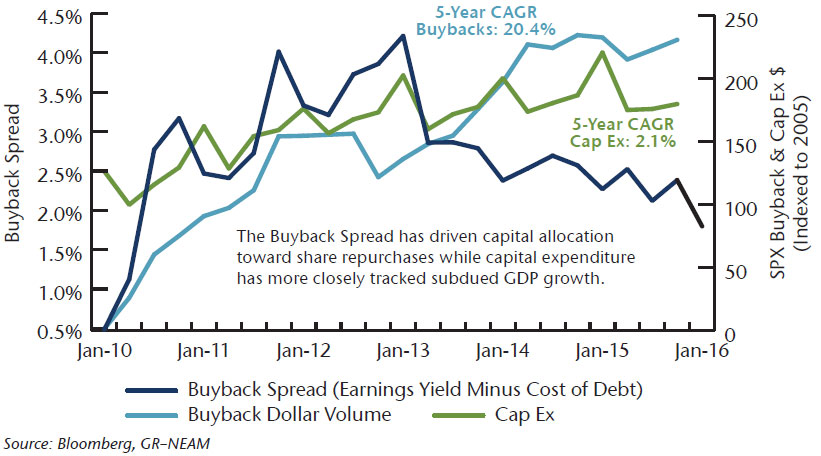

Not only has the sheer number of companies buying back stock doubled, capital allocation has been reprioritized toward share repurchase (and M&A) by the cheap cost of debt. The compelling economics are best depicted by the buyback spread (Chart 2). The buyback spread, approximated by the earnings yield of the S&P 500 minus the effective yield of the Bank of America Merrill Lynch Investment Grade Index, measured the peak differential at over 400 bps in 2013. While it is still historically “cheap” for companies to borrow, corporate bond spreads have widened since late 2014. Consequently, the differential has compressed, making it more expensive to fund financial engineering and impeding the incremental decision to lever up. If this compresses further, this has potential implications for the demand for equities.

Chart 2. Rising Cost of Debt and Financial Engineering

The heightened level of returned capital has also come at the expense of capital expenditures. Capital is allocated toward financial engineering, potentially crowding out important long term business investment and growth oriented innovation. As highlighted in Chart 2, there has been a 10-fold differential in the 5-year compounded growth rate in buybacks versus capital expenditures supporting this thesis. Capital expenditures are likewise trending well below the normalized range over the last 25 years as a percent of operating cash flow (Source: S&P Dow Jones). To the extent prioritizing financial strategies over operational ones leaves a legacy of painful opportunity costs, misallocation of capital will be debated, and the true cost only understood in hindsight.

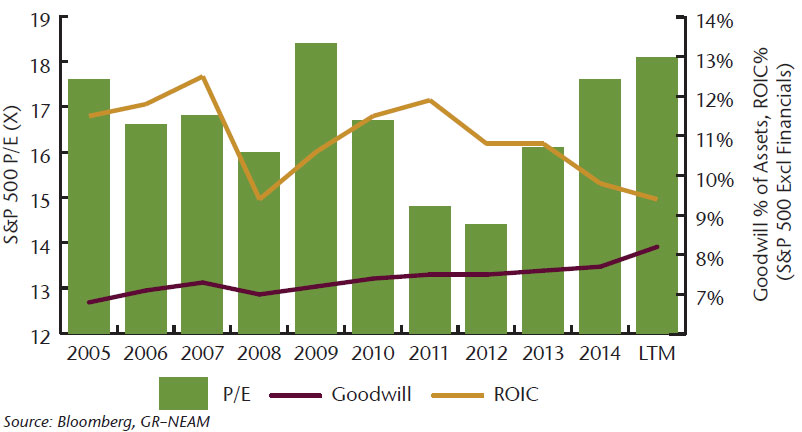

Financial engineering has also impacted the efficacy of capital allocation. Goodwill, as measured by a percentage of total assets on the balance sheets of corporate America, sits at multi-year highs. By definition, goodwill represents the value above physical assets that come with a purchase from which companies expect to drive value. While its existence is not a red flag unto itself, it merits attention when it constitutes a high percentage of total assets and financial returns are consistently low. Goodwill has doubled over the last decade and risen as a percentage of the asset base of corporate America. By no coincidence, return on invested capital has compressed over 200 bps in the comparable time period (Chart 3). While absolute returns on capital are not anemic, financial engineering has left an indelible imprint on corporate balance sheets. The next chapter has yet to be written, but the trend is not encouraging.

Chart 3. Asset Productivity

Earnings, and in turn valuations, have likewise benefited from the deployment of corporate liquidity. Share repurchase has augmented operating earnings growth by over 200 bps per data compiled by Wells Fargo, and the volume of U.S. buybacks as a share of corporate earnings before tax is approaching the 2007 peak. Just as earnings have been augmented, valuations have also rewarded financial engineering despite the decline in the productivity of assets. Currently, the market is paying more per unit of employed capital for a lower level of return, a divergence that is not sustainable, in our view (Chart 3).

Conclusion

As the Federal Reserve normalizes interest rate policy and removes one source of support for risk assets, corporate liquidity, in the form of buybacks and M&A, will be even more impactful as determinants for the price of risk assets. With the cost of funding rising as corporate spreads widen, the incentives for financial engineering remain but are diminishing. This could present a future headwind for equities. Meanwhile, the legacy of financial engineering is imprinted heavily on the balance sheets of corporate America which could likewise impede equity appreciation. As we await the elusive improvement in economic activity, we believe stock prices will increasingly reflect the underlying productivity of assets and capital deployment decisions; stock specific variables will drive returns making stock picking critical. We foresee a similar backdrop in the year ahead – higher volatility, less compensation for risk and lower implied returns for U.S .equities. As such, exposure to equities is best achieved via a portfolio constructed with stocks that are attractively priced on an individual basis which can provide some measure of downside protection when asset re-pricing occurs.